[logseq-plugin-git:commit] 2025-12-11T14:50:38.767Z

This commit is contained in:

@@ -1,51 +0,0 @@

|

||||

created:: 2024-02-05T22:36:46 (UTC -05:00)

|

||||

tags:: article

|

||||

source:: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2017/nov/24/how-the-sandwich-consumed-britain

|

||||

author:: Sam Knight

|

||||

title:: How the sandwich consumed Britain

|

||||

|

||||

- How the sandwich consumed Britain | Sandwiches | The Guardian

|

||||

- > ## Excerpt

|

||||

- > The long read: The world-beating British sandwich industry is worth £8bn a year. It transformed the way we eat lunch, then did the same for breakfast – and now it’s coming for dinner

|

||||

-

|

||||

- Notes

|

||||

- By the end of the 20th century, more people in Britain were making and selling sandwiches than working in agriculture. #Quotes

|

||||

- “Toast Sandwich” – a piece of toast, seasoned with salt and pepper, between two pieces of bread logseq://graph/LogSeq?block-id=6c29cd49-5287-4de5-a6eb-b6cf25717041

|

||||

- “It is by eating sandwiches in pubs on Saturday lunchtimes that the British seek to atone for whatever their national sins have been,” wrote Douglas Adams in 1984. #quotes logseq://graph/LogSeq?block-id=6c29cd49-5287-4de5-a6eb-b6cf25717041

|

||||

- Article

|

||||

-

|

||||

- The invention of the chilled packaged sandwich, an accessory of modern British life which is so influential, so multifarious and so close to hand that you are probably eating one right now, took place exactly 37 years ago. Like many things to do with the sandwich, this might seem, at first glance, to be improbable. But it is true. In the spring of 1980, Marks & Spencer, the nation’s most powerful department store, began selling packaged sandwiches out on the shop floor. Nothing terribly fancy. Salmon and cucumber. Egg and cress. Triangles of white bread in plastic cartons, in the food aisles, along with everything else. Prices started at 43p.

|

||||

- Looking upon the nation’s £8bn-a-year sandwich industrial complex in 2017, it seems inconceivable that this had not been tried before, but it hadn’t. Britain in 1980 was a land of formica counters, fluorescent lighting and lunches under gravy. [Sandwiches](https://www.theguardian.com/food/sandwiches) were thrown together from leftovers at home, constructed in front of you in a smoky cafe, or something sad and curled beneath the glass in a British Rail canteen. When I spoke recently to Andrew Mackenzie, who used to run the food department at M&S’s Edinburgh store – one of the first five branches to stock the new, smart, ready-made sandwiches – he struggled to convey the lost novelty of it all. “You’ve got to bear in mind,” he said. “It didn’t exist, the idea.”

|

||||

- If anything, it seemed outlandish. Who would pay for something they could just as easily make at home? “We all thought at the time it was a bit ridiculous,” said Mackenzie. But following orders from head office, he turned a stockroom into a mini production line, with stainless steel surfaces and an early buttering machine. The first M&S sandwiches were made by shop staff in improvised kitchens and canteens. Prawns defrosted on trays overnight, and a team of five came in before dawn to start work on the day’s order.

|

||||

- And, oh, they sold. They sold so fast that the sandwich experiment spread from five stores to 25, and then 105. Soon, Mackenzie was hiring more sandwich makers in Edinburgh. In the Croydon branch, a crew of seven was making a hundred sandwiches an hour. The first official M&S sandwich was salmon and tomato, but in truth it was a free-for-all. They sold so fast that staff made them out of whatever was lying around. In Cambridge, they made pilchard sandwiches, and people wanted those, too.

|

||||

- Without being designed to do so, the packaged sandwich spoke to a new way of living and working. Within a year, demand was so strong that M&S approached three suppliers to industrialise the process. (One of the world’s first sandwich factories was a temporary wooden hut inside the Telfer’s meat pie factory in Northampton.) In 1983, Margaret Thatcher visited the company’s flagship store in Marble Arch and pronounced the prawn mayonnaise delicious.

|

||||

- Every supermarket jumped on the trend. Up and down the country, chefs and bakers and assorted wheeler-dealers stopped whatever they were doing and started making sandwiches on industrial estates. The sandwich stopped being an afterthought, or a snack bought out of despair, and became the fuel of a dynamic, go-getting existence. “At Amstrad the staff start early and finish late. Nobody takes lunches – they may get a sandwich slung on their desk,” Alan Sugar told an audience at City University in 1987. “There’s no small-talk. It’s all action.” By 1990, the British sandwich industry was worth £1bn.

|

||||

-

|

||||

- Illustration: Pete Gamlen

|

||||

- A young economics graduate named Roger Whiteside was in charge of the M&S sandwich department by then. As a young buyer, Whiteside had come up with the idea of a set of four peeled oranges, to save customers time. He had read that apartments were being built in New York without kitchens, and he had a sense of where things were going. “Once you are time-strapped and you have got cash, the first thing you do is get food made for you,” he told me. “Who is going to cook unless you are a hobbyist?”

|

||||

- In the sandwich department, he commissioned new prototypes every week, and devised an ultimately impractical scheme to bake baguettes in west London each morning and deliver them, still crusty, to stores around the capital. Baguettes go soft when they are refrigerated – one of a surprising number of technical challenges posed by sandwiches. Whiteside immersed himself in questions of “carriers” (bread), “barriers” (butter, mayonnaise), “inclusions” (things within the bread), “proteins” (tuna, chicken, bacon) until they bordered on the philosophical. “What is more important, the carrier or the filling?” he wondered. “How many tiers of price do you offer in prawn? How much stimulation do people need?”

|

||||

- In the early 90s, Whiteside developed M&S’s first dedicated “food to go” section, with its own tills and checkouts, in Manchester. The innovation prefigured the layout of most contemporary supermarkets, and was fabulously successful. But it wasn’t successful enough for Whiteside. He didn’t understand why absolutely everyone in Manchester city centre wasn’t coming in to M&S for their lunch.

|

||||

- One day, he went into [a branch of Boots](https://www.theguardian.com/news/2016/apr/13/how-boots-went-rogue) on the other side of the street. Like almost every major retail chain, the pharmacy had followed M&S into the sandwich business. (Boots established the country’s first national distribution system – selling the same sandwiches in its all branches – in 1985, and pioneered the meal deal.) But Whiteside was convinced that its sandwiches weren’t as good as M&S’s, and that most customers knew that, too. He confronted the lunchtime queue in Boots and asked people why they weren’t coming to his store. “They said: ‘Well, I am not crossing the road’,” he recalled.

|

||||

- The answer struck Whiteside with great force. Mass-producing a meal that you could, if necessary, rip open and consume in the street was transforming people’s behaviour. “Instant gratification and total convenience and delivery,” Whiteside said. “If you are not there, they are not going looking for you.” He returned from Manchester and tried to persuade M&S to open hundreds of standalone sandwich shops in London. “It was so obviously an opportunity.” M&S didn’t go for the idea, but Whiteside was convinced that the future would belong to whoever was selling on every corner. He saw Pret and Starbucks and Costa and Subway coming a mile off. During the 1990s, the sandwich industry trebled in size. By the end of the 20th century, more people in Britain were making and selling sandwiches than working in agriculture.

|

||||

- ---

|

||||

- If you have been eating a packaged sandwich while reading this, you will have probably finished it by now. One industry estimate says that, on average, they take 3.5 minutes to consume. But no one really knows, because no one pays attention. One of the great strengths of the sandwich over the centuries has been how naturally it grafts on to our lives, enabling us to walk, read, take the bus, work, dream and scan our devices at the same time as feeding ourselves with the aid of a few small rotational gestures of wrist and fingers. The pinch at the corner. The sweep of the crumbs.

|

||||

- But just because something seems simple, or intuitive, doesn’t mean that it is. The rise of the British chilled sandwich over the last 40 years has been a deliberate, astonishing and almost insanely labour-intensive achievement. The careers of men and women like Roger Whiteside have taken the form of a million incremental steps: of searching for less soggy tomatoes and ways to crispify bacon; of profound investigations into the molecular structure of bread and the compressional properties of salad. In the trade, the small gaps that can occur within the curves of iceberg lettuce leaves – creating air pockets – are sometimes known as “goblin caves”. The unfortunate phenomenon of a filling slumping toward the bottom of a sandwich box, known as a skillet, is “the drop”. Obsessed by perfection and market share, the sandwich world is, unsurprisingly, one beset by conditions of permanent and ruthless competition. Every week, rival sandwich developers from the big players buy each others’ products, take them apart, weigh the ingredients, and put them back together again. “It is an absolute passion,” one former M&S supplier told me. “For everybody. It has to be.”

|

||||

- The homeliness of the sandwich has been able to mask its extraordinary effectiveness as a commercial product. In 1851, the Victorian social commentator Henry Mayhew calculated that 436,800 sandwiches, all of them ham, were sold on the streets of London each year. That might sound a lot, but Sainsbury’s, which currently accounts for around 4% of the UK “food to go” market, now sells that number every 36 hours. “It is sometimes hard to tell how much has changed with our sandwich consumption, because we feel really nostalgic towards them,” [Bee Wilson](https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/aug/11/why-we-fell-for-clean-eating), the food writer, told me. “But actually, eating sandwiches five days a week, as lots of people do now, or even seven days a week – that is what has changed. They have invaded every area of our lives.”

|

||||

- And yet the sandwich is not satisfied. You might think that, in a nation that buys around 4bn a year, and in which you have been feeling better since you [stopped eating so much bread](https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/nov/11/are-uks-leading-bakers-toast-bread-sales-fall-costs-rise), that the market might be saturated, or even falling off a little. But that is not the case. According to the British Sandwich Association, the number grows at a steady 2% – or 80 million sandwiches – each year. The sandwich remains the engine of the UK’s £20bn food-to-go industry, which is the largest and most advanced in Europe, and a source of great pride to the people who work in it. “We are light years ahead of the rest of the world,” Jim Winship, the head of the BSA, told me.

|

||||

- British sandwich-makers are sought-after across Europe, and invited to places like Russia and the Middle East to advise on everything from packaging and production lines to “mouth feel” and cress. “In Saudi Arabia they absolutely love the story of [the Earl, the scoundrel](http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-kent-18010424),” one factory owner told me. And during weeks of reporting for this article, I didn’t come across one person who doubted that the long boom would continue for years to come. “It’s big. We all do it. And we do it a lot, is our summary of the market,” said Martin Johnson, the chief executive of Adelie Foods, a major supplier of coffee shops and universities.

|

||||

- Part of what pushes the industry forwards is the maddening fact that we continue to make so many sandwiches at home – an estimated 5bn a year. “The biggie is still the people who aren’t buying,” Johnson told me. The prize that seemed so unlikely in 1980 – the industrialisation of something as scrappy as the sandwich – is now almost a provocation to people who dedicate themselves to the food-to-go concept.

|

||||

- After all, every sandwich you make at home is one they have not sold. When you talk to people in the business, they will invoke the inventory problems faced by ordinary households in supplying enough variety in salads and breads. They are also aware that, barring a dramatic change in our circumstances (around 2009, following the financial crisis, there was a brief but noticeable fall in the sale of shop-bought sandwiches), people who start eating on the move don’t look back. When I dropped by the development kitchens at Sainsbury’s a few weeks ago, there was an Oakwood smoked ham and cheddar sandwich – the supermarket’s bestseller – sitting on the table. “Twenty thousand people a day used to make a ham and cheese sandwich,” said Patrick Crease, a product development manager. “Now _this_ is their ham and cheese sandwich.” I don’t know whether he meant to, but he made this sound somehow profound and irreversible. “There are 20,000 variants that don’t exist anymore.”

|

||||

- More fundamentally, though, the sandwich has proven itself to be uniquely adaptable to our time-pressed, late-capitalist condition. In [her 2010 book](http://www.reaktionbooks.co.uk/display.asp?K=9781861897718) about sandwiches, Wilson wrote that the best way to understand it was not to think about it as food wrapped in bread, but as a form of eating – functional and transitory – that reflects how we live now. “Sandwiches freed us from the fork, the dinner table, the fixed meal-time,” Wilson wrote. “In a way, they freed us from society itself.”

|

||||

-

|

||||

- A Pret A Manger kitchen in central London. Photograph: Jonathan Player/Rex/Shutterstock/Alamy

|

||||

- Sandwich people seek to know more about us than we know about ourselves. They spend just as much time thinking about our habits and frailties as they do thinking about what we want to eat. Starbucks knows you are more likely to have a salad on a Monday, and a ham and cheese toastie on a Friday. Sandwich factories know that our New Year’s resolutions will last until the third week of January, when the BLT orders pick up again. Clare Clough, the food director of [Pret a Manger](https://www.theguardian.com/small-business-network/2015/apr/14/pret-a-manger-happy-coffee-chain), told me that the company can predict years in advance, if necessary, its busiest day for breakfast sandwiches: the last working Friday before Christmas – office party hangover morning – which this year falls on 15 December. “We can tell you now how many we are going to do,” she said.

|

||||

- The most obvious – and ambitious – plot of the sandwich industry is to make us eat them throughout the day. People in the trade, I noticed, rarely talk about breakfast, lunch or dinner. They speak instead about “day parts”, “occasions” and “missions”, and any and all of these is good for a sandwich. In 2016, the British public carried out an estimated 5bn food-to-go “missions”, and these are spread ever more evenly across the day parts. In recent years, the biggest development in the sandwich business has been its successful targeting of breakfast. (The best-selling filling of the last 12 months has been bacon.) And the next frontier, logic dictates, is dinner – or, as it was described to me at Adelie Foods, “the fragmentation of the evening occasion”.

|

||||

- Whiteside, the former Marks & Spencer sandwich man, is one person who believes that the industry can take on the night. He left M&S in 1999, after 20 years, and helped to found [Ocado](https://www.theguardian.com/business/ocado), the online supermarket. In 2013, Whiteside became the chief executive of Greggs, the UK’s largest bakery chain, where he has overseen a radical expansion and simplification of the business – opening hundreds of new stores, [drive-throughs](https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/aug/01/greggs-sees-window-of-opportunity-in-drive-through-shops) and a delivery service. Last month, he told me that he sees the hot sandwich as the key to making Greggs “more appealing in the evening day part”. If you want people to eat a sandwich on their way home, give them something warm. We were sitting in a small meeting room on the second floor of Greggs’s corporate headquarters, on the edge of Newcastle. “Think about it,” said Whiteside. “A burger is a hot sandwich, isn’t it?” He seemed pleased by this, the intimation of another day part to conquer. “Sandwiches,” he said, “never sit still.”

|

||||

- ---

|

||||

- The revolutionary possibilities of the sandwich have always been well hidden by its sheer obviousness. The best history, written by Woody Allen in 1966, imagines the conceptual journey taken by the fourth Earl of Sandwich 200 years earlier. “1745: After four years of frenzied labour, he is convinced he is on the threshold of success. He exhibits before his peers two slices of turkey with a slice of bread in the middle. His work is rejected by all but David Hume, who senses the imminence of something great and encourages him.”

|

||||

- Scholarly attempts to isolate the precise moment of incarnation – the first stack – mostly read like other parodies. There is some theorising around “trenchers”, thick hunks of bread that served as plates in the Middle Ages, and overwrought interpretations of Shakespeare’s references to “bread-and-cheese”; while everyone acknowledges the long history of flatbreads and their fillings in southern Europe and the Middle East. For this reason, there is strong interest in the Earl’s tour of the Mediterranean as a young man in 1738-39, but unfortunately he made no mention of the pitta bread or the calzone in the detailed journal that was published after his death.

|

||||

- The first definite sandwich sighting occurs in the diaries of Edward Gibbon, who dined at the Cocoa Tree club, on the corner of St James Street and Pall Mall in London on the evening of 24 November 1762. “That respectable body affords every evening a sight truly English,” he wrote. “Twenty or thirty of the first men in the kingdom … supping at little tables … upon a bit of cold meat, or a Sandwich.” A few years later, a French travel writer, Pierre-Jean Grosley, supplied the myth – beloved by marketing people ever since – that the Earl demanded “a bit of beef, between two slices of toasted bread,” to keep him going through a 24-hour gambling binge. This virtuoso piece of snacking secured his fame.

|

||||

-

|

||||

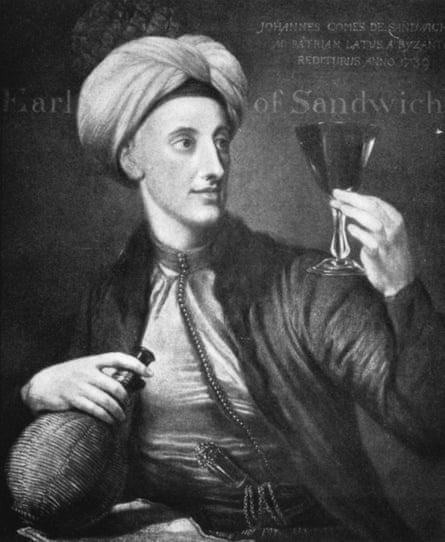

- John Montagu, the fourth Earl of Sandwich, in a 1739 painting by George Knapton. Photograph: Alamy

|

||||

- The evidence for this, though, is weak. In his definitive biography, The Insatiable Earl, published in 1994, NAM Rodger concludes that Sandwich was hard-up, and never wagered much for a man of his rank. A large, shambling figure, prone to breaking china, the Earl ran the Admiralty, by most accounts badly, for a total of 11 years. He lived alone after his wife went mad in 1755. Visitors to his house remarked on the poor quality of the food. “Some of his made dishes are either meagre or become absolutely obsolete,” said his friend, Lord Denbigh. The likely truth is that the entire future of the sandwich – its symbiotic relationship with work, its disregard for a slower, more sociable way of eating – was present at its inception. In 18th-century English high society, the main meal of the day was served at around 4pm, which clashed with the Earl’s duties at the Admiralty. He probably came up with the beef sandwich as a way of eating at his desk.

|

||||

- The fad was soon unstoppable. Louis Eustache Ude, the chef d’hotel to the Earl of Sefton, acknowledged the power of new format in his cookbook of 1813. A generous spread of sandwiches “of fowl, of ham, of veal, of tongue, &c., some plates of pastry and here and there on the table some baskets of fruit” – a textbook food-to-go offering, in other words – could cut the costs of a dinner and dance by three quarters. But it was demeaning, too. Chef Ude did his best to refine the craze, suggesting bechamel as a barrier and urging “extraordinary care” in the trimming of salad, but you can sense in his words the frustration that he has been reduced to this. “Of all things in the world, sandwiches have least need of explanation,” he wrote. “Everyone knows how to make them, more or less.”

|

||||

Reference in New Issue

Block a user